Trusts (or trust funds) are one of those financial planning terms that starts to feel diluted over time. People have a general sense of what trusts are, but many would be hard pressed to define the specifics. Given how important trusts can be to a strong financial, estate, and tax plan, we want to spend some time getting into the details and specifics of trusts. We’ll cover what trusts are (and how they work) as well as common types of trusts and when you might consider using them.

What is a trust?

A trust is a legal arrangement where a trustor (owner of assets) transfers those assets to a trustee who manages them on behalf of a beneficiary.

The trust refers to the fund, account, vehicle, or legal documents surrounding those managed assets. For instance, a building might be owned by a trust, assets might be placed in trust, and so on.

Generally speaking, the trustor selects a trustee to manage the trust. In some situations, the trustor acts as trustee. Other times, the trustor selects a trusted colleague, friend, or family member, or even a professional trustee to make sure things are managed properly.

Revocable versus irrevocable trusts

There are dozens of types of trusts, many with specialized use cases. However at the highest level, trusts fall into two main categories: revocable and irrevocable.

As the name implies, you can revoke, undo, and otherwise alter a revocable trust. These documents are often used as an estate planning tool, as they can help families avoid probate and allow for more flexibility (with fewer updates) than a will. They are sometimes referred to as living trusts.

The reverse is true for irrevocable trusts: You generally cannot undo an irrevocable trust once it’s created and funded. Once you pass assets to an irrevocable trust, they are owned by the trust. These trusts are often used for estate planning and wealth transfer purposes, since the assets are no longer in your estate once they’re transferred to the trust. However, this transfer also comes with a loss of control, generally speaking.

Additionally, the assets in an irrevocable trust don’t get a step-up basis on death. This can be complex in relation to property and capital gains taxes, particularly with real estate. A tax or financial advisor can help you better understand the implications.

As you might expect, the devil is in the details. There are numerous types of irrevocable trusts, many of which build certain elements of flexibility into the terms.

Types of irrevocable trusts

Irrevocable trusts can be structured differently to help you achieve specific goals. Let’s review a few of the more commonly-used types of irrevocable trusts.

Life insurance trusts

Families with significant wealth who are worried about estate and/or inheritance taxes might use a life insurance policy to help cover any potential tax burden for their heirs. In other words: These families would take out a life insurance policy where the death benefit is large enough to cover the anticipated tax bill.

Of course, the cash value of this type of life insurance policy could be factored into the value of the estate, thereby increasing a potential tax burden and otherwise detracting from your overall objective. That’s where a life insurance trust comes in—you can place any such policy into an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT), thus removing it from the taxable estate.

While a life insurance trust can help you get strategic about paying for an estate or inheritance tax, some trusts can help you avoid paying an estate tax altogether.

Dynasty trusts

These irrevocable trusts are designed to help families preserve wealth across multiple generations, as the name implies. Once assets pass to these irrevocable trusts, they no longer count towards your taxable estate. Families can fund these trusts strategically to avoid triggering the annual gift tax threshold as well as the lifetime exemption. Funding these trusts early means the assets can grow separate from the estate.

In other words, if you put $13.9M (just under the lifetime estate tax exemption) into a dynasty trust in 2025, that money would grow separate from your estate. The trust could be worth $100M when you die, and it still wouldn’t trigger the estate tax.

A few things to keep in mind:

– The assets in trusts don’t grow tax free; they just aren’t considered part of your estate.

– Beneficiaries may need to pay taxes on distributions from a trust, depending on whether they are withdrawing principal or income.

– How long a dynasty trust can last can vary significantly by state—some allow you to create these trusts in perpetuity where others have a much shorter timeline.

GRATs

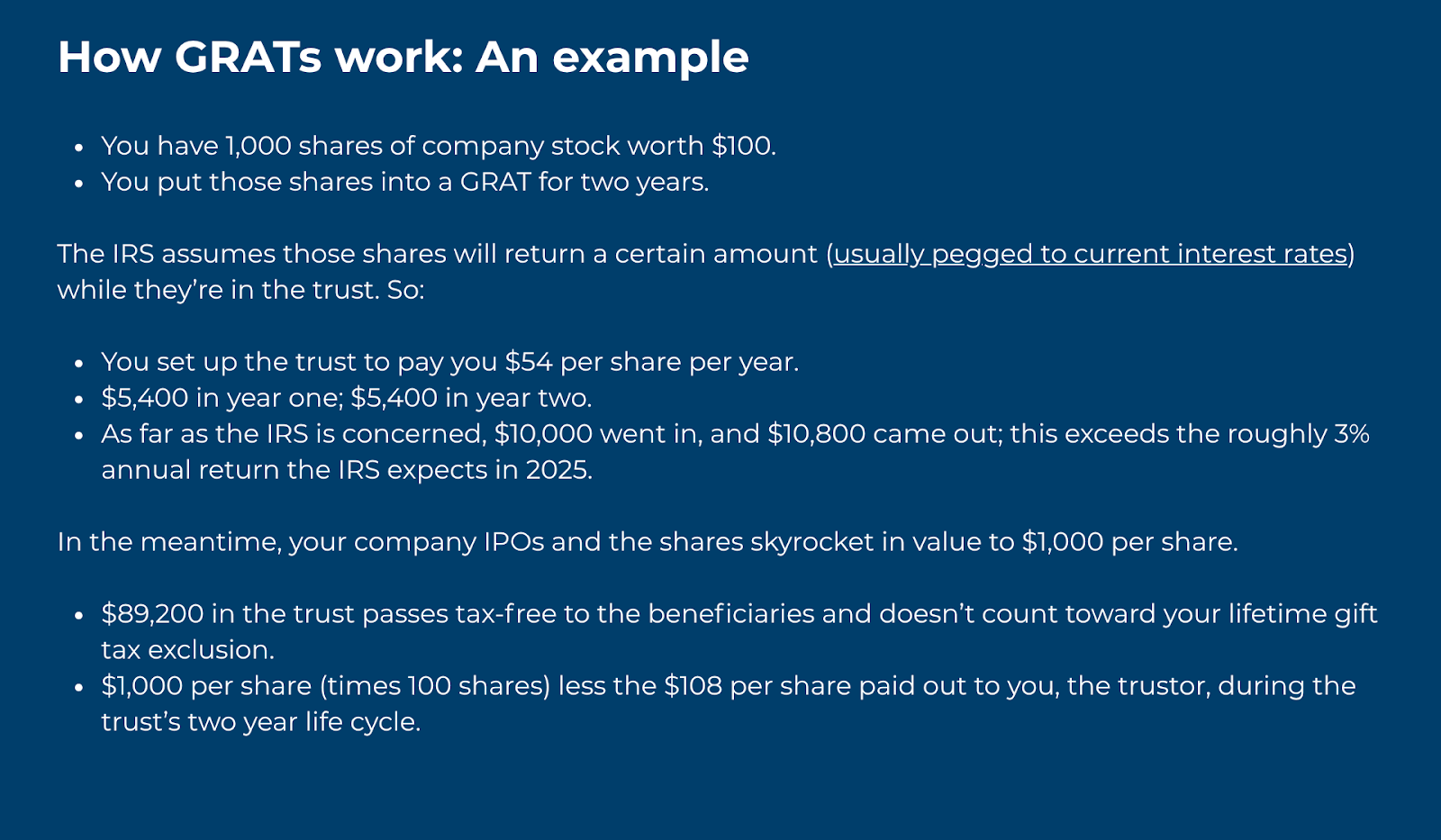

Grantor retained annuity trusts (GRATs) are set up such that the trust can pay an income (or annuity) to the trustor—the person who set up the trust—over a specific period of time, usually a duration of a few years. After that period, the assets in the trust pass to the named beneficiaries.

GRATs are similar to dynasty trusts in that they create a tax-optimized way to pass wealth to the next generation. However, these trusts are much more specific in their design; they tend to be used ahead of a big-money event like the sale of a business or a company IPO.

SLATs

Spousal lifetime access trusts (SLATs) are another tax optimized way to pass wealth to the next generation while still allowing the trustor some access to the funds, via their spouse. With these trusts, the trustor irrevocably transfers a set amount of assets to a trust that their spouse can access throughout their lifetime; when they die, the assets will pass to the trust beneficiaries.

The IRS prohibits reciprocal trusts—meaning you can’t pass your assets to a spouse via a SLAT… only to have them create a SLAT that benefits you. These trusts are also irrevocable, so your spouse will continue to benefit from a SLAT you set up even if you separate.

The IRS monitors these types of trusts closely so it’s important you understand both the rules involved and the design of your specific trust document.

Charitable trusts

You can set up trusts designed to benefit specific charities or causes you care about. You may be able to combine this endeavor with other financial goals.

- A charitable remainder trust is set up to benefit someone for a set time, such as you, the trustor, your spouse, or your heirs. Once that period ends, the remaining assets get distributed to a qualified charity.

You can also take the opposite approach.

- A charitable lead trust establishes a trust that will make preset payments to a qualified charity for a prescribed period. Once that window ends, the remainder of the assets in the trust are distributed to heirs or other beneficiaries.

Special needs trusts

Special needs trusts can help you financially support someone with special needs without disqualifying them from government benefits or other aid. When you set up and fund an irrevocable special needs trust, the trust owns the assets for the benefit of the beneficiary. This is a key distinction—if you simply left the assets to the beneficiary directly, their net worth might be impacted such that it would disqualify them from benefits and programs designed to support them.

Generally, there are restrictions on how the funds within a special needs trust can be distributed and spent. However, the use cases may be more diverse than other public benefits. For instance, you might be able to use the funds in a special needs trust to pay for therapy, education, and assistive technology that wouldn’t be covered under Medicare or Medicaid.

Usually, the trustee is responsible for documenting the withdrawals and expenses, as well as whatever recordkeeping is required to ensure the trust is being handled properly.

Choosing and setting up a trust

These are just a handful of the more common irrevocable trusts we see. Which you use, and how, will likely depend on your personal goals and circumstances, as well as logistics—like which state you live in or potential changes to tax the code.

The rules around how trusts are created and governed can be complex. Even moguls like Rupert Murdoch can struggle with wanting to retroactively change the terms of an irrevocable trust. As such, it’s critical to work with a team you trust. That team should probably include:

- An attorney that specializes in estate planning. The laws around estate planning are very specific and very localized. Plus, rules and regulations are only one part of the equation. The trust itself is a legal document, meaning you must follow the rules that you agree to. Make sure your lawyer understands your objectives, and how to design and optimize these objectives, including any administrative requirements.

- A professional trustee. Trustees deal with far more responsibilities than, say, the executor of a will. Managing an irrevocable trust comes with significant paperwork (such as tax filing) as well as regulatory documentation. Professional trustees charge a management fee to cover these logistics; this is usually paid directly from the trust.

- Financial advisors can be brought in to manage the assets within the trust. Your trustee may not specialize in investment management, for example, and may bring in a separate advisor to make sure investments are handled in accordance with the terms of the trust.

- A certified professional accountant who specializes in tax to ensure the numbers work across personal, business, and trust finances. They will also be responsible for filing paperwork (such as tax returns) for the trust each year. You may even want to consult a tax attorney to ensure everything is in order.

If you have questions about which of these trusts might make sense for you, or want help getting started, set up a consultation today.