When it comes to investing, you sometimes hear the phrase “big money” thrown around. That term loosely refers to institutional investors—large funds managed on behalf of an institution or group of people. These “big money” funds, which include university endowments, pensions, sovereign wealth funds, and so on, often manage enough capital that they have the power to move the market if they make big updates to their holdings. They also tend to report higher-than-average returns.

Of course, past performance doesn’t predict future results, and big money funds have had some big misses in the past, but generally speaking, institutional investors benefit from long (often indefinite) timelines and asset allocation strategies that go far beyond traditional diversification. This is partly because their size and time horizon allow them to take on more risk than the average individual investor.

Still, there are lessons for individual investors who take the time to study what the “big money” is doing.

University endowments

To help explain how universities manage their money, we’ll look at the Yale endowment as an example. The endowment is the school’s single largest source of revenue, accounting for roughly one third of its annual budget. According to the endowment’s annual report, it earned a 5.7% investment return, net of fees, for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2024.

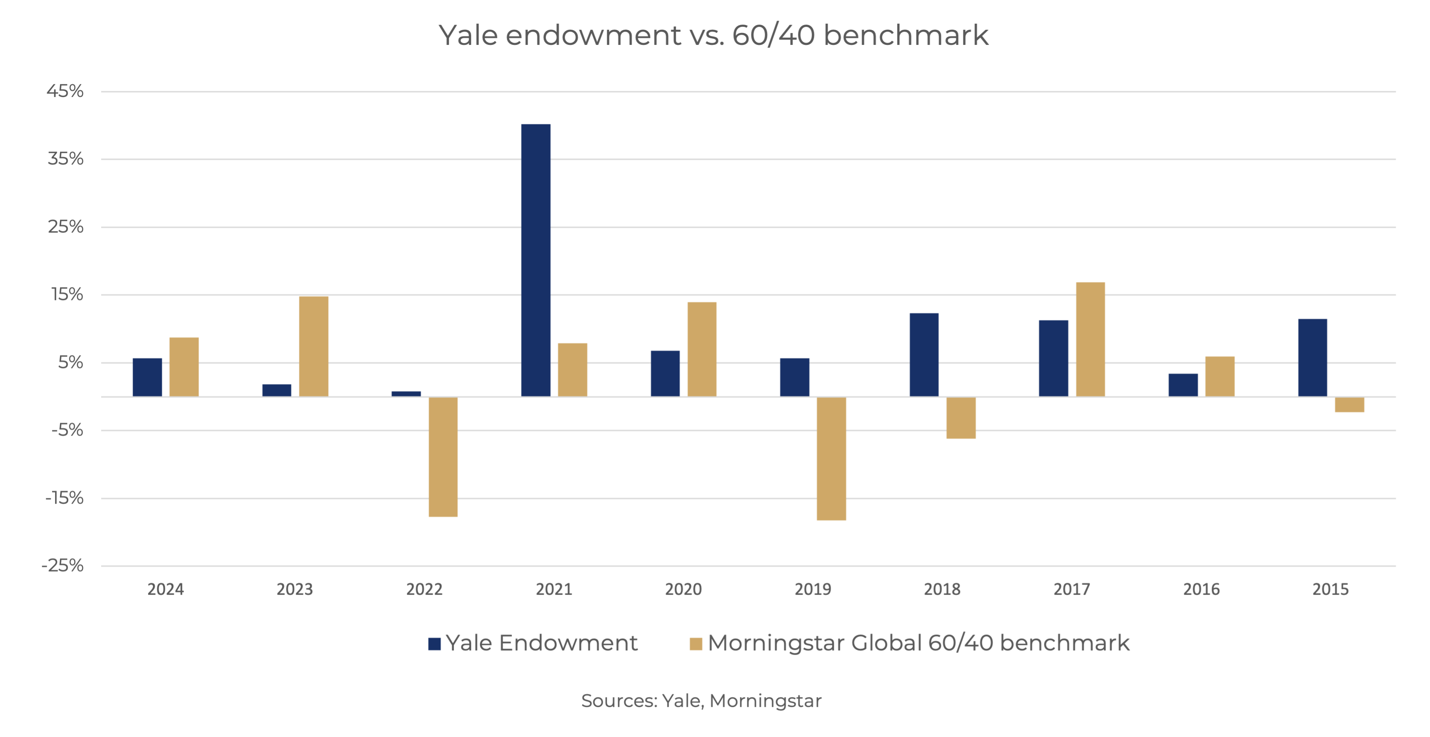

That may seem low compared to the S&P 500 which returned more than 20% over that same period, however there’s a few things to consider. First, the university isn’t an all-stock portfolio, it uses a 60/40 allocation as a benchmark (60% stocks, 40% bonds). Consider how the endowment compares to that benchmark.

Over a decade, this is a 9.5% per annum return, significantly higher than the Morningstar benchmark, and it also had no down years. Over 20 years, the returns averaged 10.3%.

So how did Yale manage to beat the benchmark? Let’s consider a few things. First, Yale has a lot of money to work with—the endowment is valued at more than $40 billion. But not all of that money is investible; the vast majority must go to specific causes or departments.

When it comes to investing, the endowment is famously tight-lipped. Less than 1% of the endowment’s money is publicly traceable through the school’s filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. This comes down to a simple factor: Yale favors private market investments, and 99% of the fund is in private companies and distributed to private asset managers.

In some ways, Yale pioneered the current approach to university endowments in the mid-1980s. This focus on alternatives, including hedge funds, venture capital, real estate, natural resources, and other private equity can lead to underperformance during bull markets, as it can be harder to exit private positions. However, it can lessen the blow of major downturns, like those we saw in 2022 and 2019.

Other universities took note; this model is now popular with other Ivy League schools including Harvard (9.6% return in 2024) and Columbia (11.5% in 2024).

Pension funds

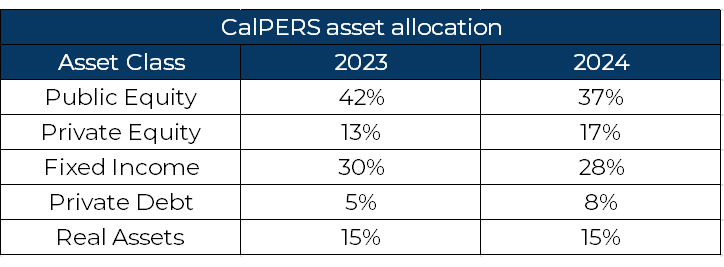

Pension funds take a similar approach on an even larger scale; they lean heavily on alternative investments to try to meet their liabilities to pensioners. In particular, pension funds seemed to focus on private debt in 2024. The California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS), which serves two million members, said it would increase private-debt allocation (from 5% to 8%) and its private-equity allocation (from 13% to 17%), pulling those funds from public market allocations.

The strategy seemed to work; CalPERS reported a preliminary net return of 9.3% on its investments in the year ending June 30, 2024. (Its overall assets top $500 billion.)

CalPERS has 12 individual funds under its umbrella. To help understand how these updated allocations played out, we looked at a single fund—the Public Employees Retirement Fund (PERF)—for the year ending in November 2024. Looking at PERF, we see that publicly traded stocks (which include derivatives), returned 17.5%, followed closely by private debt at 17%. In contrast, public debt (or fixed income) yielded just 3.7% while private equity gained 10.9%.

Beyond overall allocation, CalPERS made a commitment to clean energy as part of an overall investment strategy they hope to implement by 2030.

Sovereign wealth funds

The largest wealth fund in the world is the Norway Government Pension Fund. As of November 2024, the fund was valued at $1.7 trillion (U.S.). The valuation comes from over 11,000 investments across 71 countries.

Their overall asset allocation more closely resembles a traditional portfolio, partly because the Norwegian government regulates what the fund can invest in. For instance, the fund managers applied to invest 5% of the fund into private equity in 2024, but the government denied the petition. Norway is primarily invested in equities (72%), followed by fixed income (26.1%), unlisted real estate 1.7%, and renewable energy infrastructure accounts for 0.1% of all investments.

Most of the diversification in this fund comes from location—Norway invests in stocks across 66 countries, holds bonds from 49 countries, owns real estate in 14 countries and invests in renewables in four countries.

Other key takeaways:

- Wind energy. Norway’s commitment to renewable energy is primarily focused on European wind farms. The investment is fairly new (started in 2021) and focuses on the Netherlands, Spain, Germany, and the UK.

- Real estate. The majority of the fund’s holdings are in office space across Europe, the UK and the US, but the fund holds several retail holdings as well.

- Government vs. corporate debt. Norway invests heavily in government debt—it’s 70% of their allocation. Specifically, the fund holds roughly $130 billion in U.S. government bonds. Norway also allocates to corporate bonds and securitized debt (roughly 30% of its fixed income allocation).

- Equities. While the Norwegian approach to equities is more traditional (using publicly traded companies) the fund does use derivatives and other strategies to try to enhance returns.

Keep in mind, these funds aim to make investments that will benefit the country overall. In Norway, this means an allocation to renewable energy, but in the middle east, this has historically meant oil and gas, with gulf countries branching out to investments in sports, gaming, and renewables.

The same can be said about U.S. states; while the federal government doesn’t have a wealth fund, a handful of states do. The largest is the Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation, a $67-billion-dollar state owned investment fund that pays an annual dividend to eligible residents of Alaska.

What does it mean for the rest of us?

A recent study from DALBAR stated individual investors underperform the S&P 500. Investors often try to time the market, and shorter time frames mean a single down year (like 2022 or 2019) can derail an individual portfolio concentrated in stocks. Institutions use time and capital to take additional risks.

If you’re in a position where you don’t need extensive liquidity, or can make do with interest and yield payments, allocating more money to private markets could help smooth the effects of volatility. Of course, not everyone can invest in alternative assets and private markets—there are regulatory restrictions on who can invest and many funds come with a minimum initial investment.

If you’re curious about adapting any of the strategies mentioned in this article into your personal portfolio, from real estate to alternatives, set up a time to discuss.